There is something to be said for the idea of home, for taking photographs in it.

On one hand, we have a collection of objects put together in a space, taken control over, made to bear witness to our lives over time. A chair, a bed, a desk that has probably seen hours of failure and some amount of laughter and a good measure of despair over the years. And then we have this idea of the photograph- a sliver of time frozen, disconnected from the story that would come after it, as proposed by Berger. A photograph that captures a tiny fragment of the subject before it, divorced from the events that made it or the time that would change its meaning.

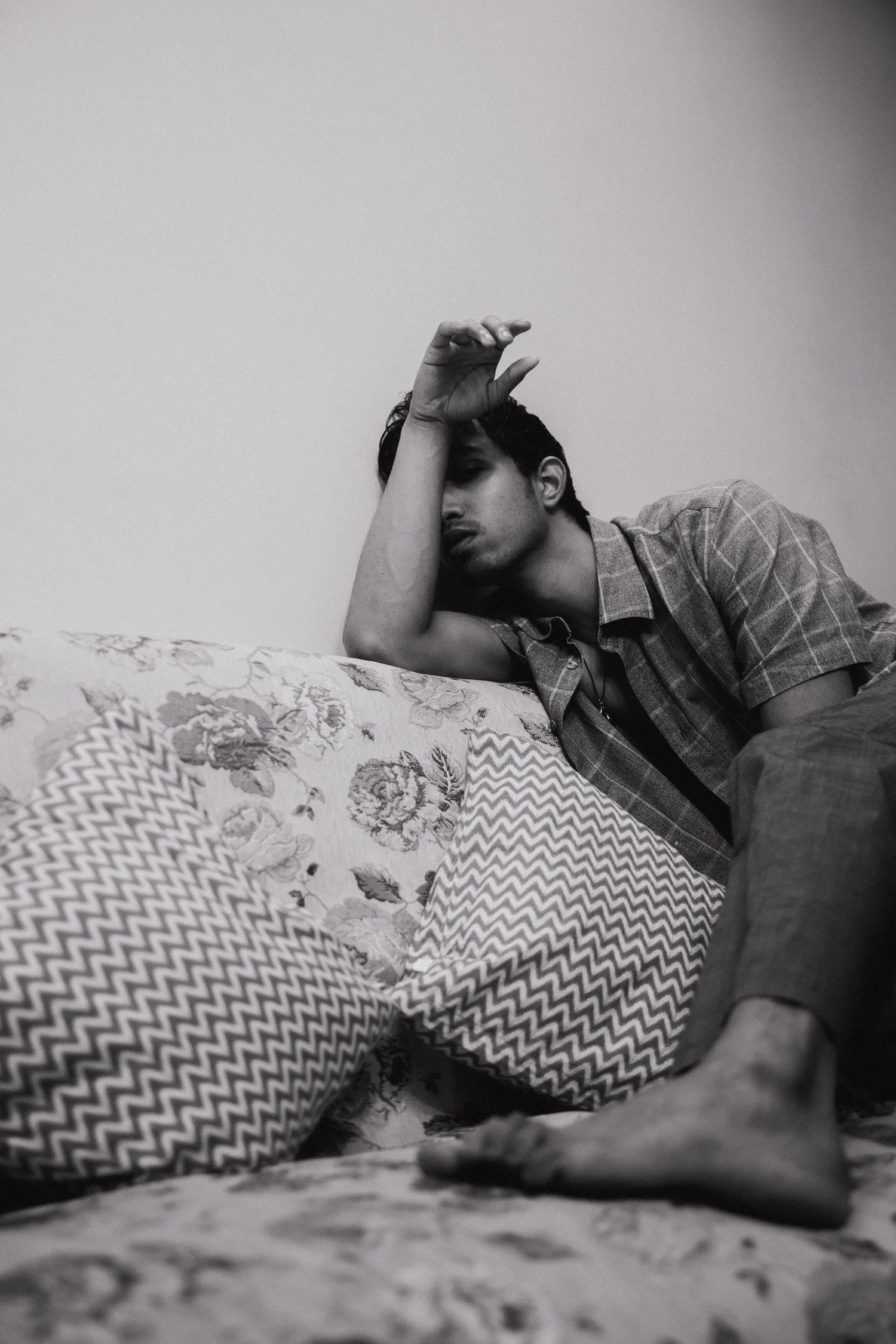

So when we put these two things together- a space so intricately intertwined with the history of a person and a device that manages to strip this element away from itself, the result is somewhat strange. We’re left with a photograph of a person surrounded by things that should give us previously untold information about them, but information that can only be limited in what it tells us. Context placed carefully in limited context. The mundane, the everyday being elevated to the position of “beauty” because someone has bothered to take a picture of it. There must be a reason that someone has bothered to take a picture of it. It must be beautiful.

And really what beauty can a photographer (and their mysterious eye) see here? What are they looking for, surrounded by tables and chairs and a bed that knows more about the person before them than they ever will? The case for shooting at home very rarely lies in the glamour of blankets or the harshness of the tubelight overhead. Worse still, the nightmare of every YouTube lighting tutorial that Brandon’s home produced so well: mixed lighting. Daylight, tungsten light, tubelight light all sitting together under a roof like best friends.

It is in the simple fact that you’re taking photos in somebody’s home, and home begins by bringing some space under control. This space that we thought we controlled then goes on to shape the body, force it to give way in as many ways as the body has shaped the space, to move as the home allows it to. While taking photos of Brandon, his home did a bulk of the work:

Picture a body moving slowly, smoothly through a room that is unfamiliar to me. A graceful twisting of the torso, a subtle duck of the head, a quick hand extended to straighten out a perpetually slanted picture frame- movements that are impossible for me to ask of someone in a place that doesn’t know them at all.

Dogs that cannot be coaxed off the bed by someone they know any lesser.

I’ve been shooting people in their homes for a few months now and it would be a lie to claim that it has always been by choice. I’ve thrown around the word “location???” more times than I can be bothered to recall, and have often hated the work that comes out of it.

But there are two things that have remained constant through it all: the sudden awareness that the bedroom I’ve spent four hours of my life in has seen another life go on for years, and the resignation that accompanies the image finally produced. Frozen in time, snatched away from its story, waiting quietly on my camera screen as if sent there to be punished.